By Tyler Pruett

tyler@southerntorch.com

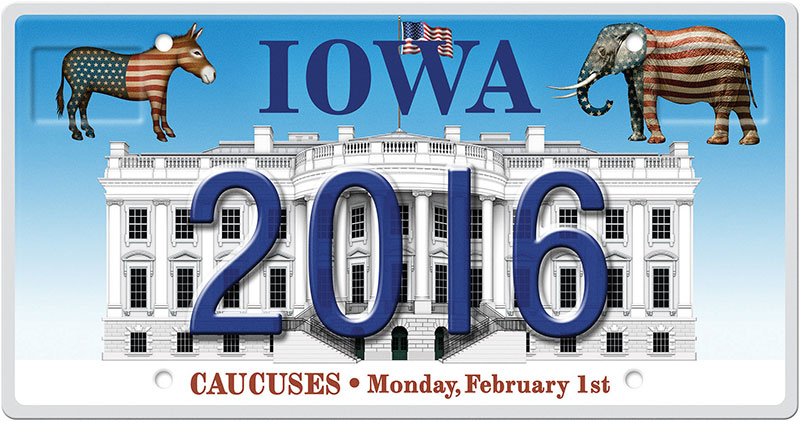

Feb. 1 marks the first electoral event for the 2016 Presidential Elections. Voters in the Hawkeye state will elect delegates in the first step of a four-step process in selecting nominees for each party. The Iowa Caucus is unique from all other states and can be difficult to understand. Some criticize it as outdated and overly complicated, while others praise it as a good example of grassroots democracy.

Defining the caucus

By definition, a “caucus” simply means a gathering of a political party to decide on delegates and party platforms. The state has used this system even before achieving statehood in the mid-19th century. Iowa changed to a primary system in the 1916 elections, but quickly changed back to the traditional format after the new system was deemed expensive and turnout was low.

For much of the century and a half the caucus has been in existence, it was mostly only attended by party activist and the elites of each precinct. The parties convened in private residences with meeting times not being disseminated to the public, excluding rank-and-file party members. In the early seventies, the Democratic National Committee set new guidelines for its party in Iowa in an effort to make the process more transparent and inclusive.

The Republicans soon followed suit with the same goals, although each party maintains a different process on caucus day. The rule changes would require thirty days to elapse between each of the four steps in the caucus-to-convention process. This effectively placed Iowa first out of the fifty states in the nominating process. Feb. 1 only begins the process with the precinct level caucuses which are followed by the county conventions held on March 12. The dates for the last two events, the district and state conventions, vary between each party, but are held in April and around the last of May/first of June.

Precinct Caucuses in the Hawkeye State

The precinct caucuses are generally held in public buildings such as schools or libraries, with in some instances the parties convening just across the hall. Voters who attend the caucus must be registered to that specific party, but registration may be done at the door upon entering. In these ways the procedures for both parties are the same, but differ in almost every other. The main difference between the two being that while the Democratic Party selects delegates based on the amount of representation a candidate gets, the Republicans conduct a “straw poll,” but elect delegates separate from the amount of votes a candidate receives. This results in the Democratic caucus being more complex and generally taking over two hours in comparison to the Republicans’ roughly one hour.

The Republican straw poll is conducted shortly after the caucus is called to order, with votes being written on scrap paper or a ballot provided by the local party. Prior to the ballots being cast, the attendees are asked if anyone would like to speak on a candidate’s behalf. Speeches given are short; with the speaker only stating who they are supporting and why. Once the votes are counted, the elected county chair phones the results to the state party. This is primarily because of the large amount of national media coverage, as the poll results have no bearing on the election of delegates. After the conclusion of the polls, county delegates are elected by those in attendance. While candidates for delegate may receive more or less votes based on their personal preference for president, delegate selection does not necessarily represent the popular sentiment among the Republican caucus-goers.

As previously stated, the Democratic process involves electing the delegates based on the amount of support each candidate receives. If 500 voters attend a Democratic caucus and are allocated 20 delegates total, each presidential candidate will receive the same percentage of delegates as their percentage of total votes from the original pool of 500. So if Hillary Clinton, for example, receives the support of 150 attendees out of 500, she receives 30 percent of the delegation, or 6 delegates out of 20.

Candidates must meet what’s referred to as the “viability threshold” to be eligible to receive any delegates. This threshold is 15 percent of support among the total voters in attendance. In our example caucus of 500 voters, a candidate must have at least 75 supporters to send delegates to the county convention. This makes it necessary for the first order of business at the Democratic caucus to be determining how many voters are present. While this sounds simple, counting hundreds of people in a school or library can be chaotic.

Once the headcount is completed and the viability threshold is established, the caucus moves into the “first alignment” phase. During this time, the attendees split up into different parts of the room, forming “preference groups” for each candidate. Each campaign has leaders assigned to their respective precincts, who attempt to draw as many people as possible to their group. After about thirty minutes, the first alignment is concluded and a count is done of each group. The caucus chair then determines which groups meet the threshold and announce the results.

After the first alignment phase comes “realignment.” This gives another thirty minutes for nonviable groups to either join another group or convince others to join them in support of their candidate in order to make them viable. Many individuals engage in debate in order to draw voters away from other candidates. After realignment, the preference groups are counted as during the first phase. For any groups that still remain nonviable, they are given a third and final chance to move to a viable group before final support is counted.

After getting the final numbers, the caucus chair allocates each viable group delegates according to the percentage they received. It’s interesting to note that while the amount of delegates received by each candidate is reported, raw numbers of supporters are never reported to the state party during the process.

How to win in Iowa

Though each party’s caucus procedures differ, candidates from both must focus on grassroots organizing as their best strategy in Iowa. The Iowa system requires participants to not only be physically present, but to also actively take part in the process which consumes more time than simply voting in a primary. This means that campaigns must actively recruit motivated supporters and ensure they arrive at their dedicated caucus location. A successful campaign in Iowa needs large amounts of volunteer support in order to identify supporters by door-to-door campaigning or phone calls.

The complexity of the Democratic process translates into a more complex strategy to achieve victory for the candidates. While Republicans can focus only on getting supporters out on Feb. 1 to elect delegates favorable to their campaign and showing viability in the straw poll, Democrats must have a very organized presence at each precinct caucus. Each candidate precinct leader has to be able to engage voters, well represent their candidate, and maintain order amongst the chaos of alignments. Many leaders even bring incentives, such as sandwiches or desserts to draw caucus-goers to their group. And with the delegates being distributed proportionally at each nomination event, Democratic party candidates may have to return to Iowa for the county, district, and state conventions if the race is close.

One little known irony of the Iowa nomination process is that while being the first event of the presidential election, the official delegates for the state are not assigned until early summer, making the state one of the last to decide on nominees. In the grand scheme of things, Iowa is the first test of viability for a presidential campaign. A strong performance here is more critical for bottom-tier candidates, or candidates not present on the main debate stage, than for those who enjoy large amounts of support. Receiving little support in the GOP straw poll or not meeting the viability threshold in the Democratic caucus can be catastrophic for fundraising, and with voters following the results nationwide, a poor performance in Iowa can translate to less support in conventional primary states which all vote after Feb. 1.

Pro’s and Con’s of a Caucus

Pundits and political scholars have varying opinions on the effectiveness of the Iowa nomination process in adequately reflecting the will of the people. The process itself makes in-depth analysis of the results more complicated than a standard primary election, in-turn making advantages and disadvantages hard to identify. Many point to the fact that since the Democratic Party rounds the raw percentages of support (if the number of delegates earned is for example 5.2, a candidate cannot be award two-tenths of person, so they earn 5 delegates) many votes are not represented, while on the Republican side, none are represented since the straw poll does not determine delegate selection. The caucus system also provides no means for absentee voting; since the whole process hinges on attendance at the meeting. Democratic voters also have no means to maintain the secrecy of their vote.

Proponents of the caucus system point out that the process is much more involved than simply showing up and casting a ballot. Individual voters become more involved in their local parties and have an opportunity to organize with like-minded people. Also, according to analysis by the University of Chicago, most participants consider the caucus meetings to be “fun and exciting” compared to normal primary voting. It’s also one of the few places where a seventeen year old can vote, providing his eighteenth birthday is on or prior to the date of the general election in November. Democratic caucus-goers in Iowa are also unique in the sense that they are allowed to make a second or even third choice.

One aspect that alway accompanies the Iowa caucus is the calls for it’s demise. Every presidential election cycle, political analyst question it’s accuracy in the media and predict that it will not exist the next time the country selects a new leader, and in every presidential election cycle we return once again to Iowa. If being able to withstand criticism is any indicator, we can expect to begin every presidential nomination in Iowa for the foreseeable future.